Ill Prepared Glacier Park Hikers owe their lives to rescue workers . . .

How in the world does the U.S. National Park Service and the media depict two guys, anyone, who gets lost outdoors and survives a difficult or even life-threatening situation, as heroes? Neal Peckens and Jason Hiser owe their lives to the rescue efforts of various teams from in and around Glacier National Park. The duo likely would be dead today if not for the bravery and heroism of those who put themselves in harm’s way to find them. The two men were recently rescued after spending five unexpected nights, four huddled together on the shoulder of a mountain at 6,000 feet, along the continental divide in Glacier National Park.

Glacier National Park’s Chief Ranger Mark Fouts in a press release October 16, 2012, said, "These hikers were prepared with appropriate equipment and they used their situational awareness skills to determine how to respond to the unexpected stay in the backcountry."

I usually discount Monday morning quarterbacking, but in this instance, I think there’s a more meaningful lesson to be learned than saying, “Good job guys you did the right thing by staying put.”

Situational awareness is about the "now," but it starts well before you find yourself in a wreck, it includes making wise decisions long before you have no choice but to wait for rescue.

A recent Christian Science Monitor article compared the adult’s situation to that of an 8-year-old child who ran too far along a trail and was lost for an hour. The child didn’t know the standard recommendation for anyone lost, which is to STOP: Stop, Think, Observe and Plan. Seemingly, that’s what Peckens and Hiser did, but knowledge is preparation and being unprepared and surviving is not heroic. It’s luck.

So while people all across the country are praising the two for staying put when lost, I’m confounded. Why the lack of attention to their failures? And why the limited accounting of the real heroes, the brave men and women who were out there on foot and horseback, and in the air looking for the men?

Let’s look at this from the perspective of a lifelong, experienced, back-country mountaineer and a person who’s been to the exact locations as these hikers many times. I understand what that environment is like, I’ve been there. I've lived in the Two Medicine Valley, just miles from the incident for 11 years. As happy as I am that they are alive, they failed the first rule of backcountry travel, especially when weather issues are a concern. That first rule is preparation. The men weren't prepared. Mistake No. 1.

It is obvious to me the men have some experience, after all they did survive five nights longer than they had planned. But is this really what we consider preparation and having, in the words of Mark Fouts of the National Park Service, “situational awareness”? The two were not as prepared as they should have been. Donning expensive, lightweight parkas, strapping on high-tech boots, and throwing some nature bars into a pack is not, in my view, being prepared - especially when you're trekking to 7,500 feet along the Continental Divide in Glacier National Park in October!

Reports indicate the two lost their map, that's mistake No. 2. Foul up No. 3, deciding to continue to travel terrain and conditions they weren't prepared to handle. They attempted to ascend a part of the trail, that by their own account was snow covered and as it turns out, much too dangerous for their skill level and or the gear they had with them. At that point, turning back is the proper decision. Being prepared is about knowing the risks, knowing personal limits, and basing decisions on those factors. The men stated they go lost when they lost the trail. With snow on the ground, what did they expect, route markers and signs along the way? These two men took a chance, in a place they clearly did not know enough about. Had it been a nice summer day with an open trail, I'd have said go for it. Not in October, at elevation, in the wilderness. Once the duo reached the section of the trail where snow began to hinder their efforts, again, they should have turned back! They were just a five or six mile hike down a flat glacial valley to the warmth and safety of their automobile and the road out. It seems their urge for adventure and lack of preparation got to them and made them decide to leave Old Man Lake area and safe exit. Next they hiked though the steep snow crusted rocks and that almost cost one of them them their life. In addition, their poor decision and lack of preparation put over 50 searchers at risk.

Being prepared means you know your limits. I think these guys would agree. Had they known where they were and yes, drawn mental maps of basic escape routes as they traveled (and in case they lost their map), they could have either turned back and walked out the Dry Fork from Old Man Lake, or after descending into the Nyack drainage to Nyack lake, they could have continued down the valley and found the large maintained trail that leads to Highway 2. Granted, the latter is a longer hike, but they would have been safer. They would not have continued to put themselves in a life threatening situation, nor caused a huge incident that required others to risk their lives and use up rescue resources.

Instead, they went higher trying to find their way back to the Two Medicine Valley! They went up and further increased their risk of dying - this AFTER they knew they were lost, and after they had almost slid down the mountain though ice and snow. That’s not being prepared, that’s not “situational awareness,” that’s being unaware of the risks and foolish. It seems to me that they did not really stay put until they wound up in a place where they had no other options. They were ill prepared, made poor life and death decisions, and did not have a severe weather emergency plan in place. They clearly had not set any basic ground rules for a bail plan. A bail plan is the emergency escape route and actions taken in used in worse-case scenarios. They apparently did not have a plan. They were not prepared.

As to their heralded situational awareness, had they stayed at the lake, once they knew they were lost, they would have been found days sooner. They didn't seem to be aware at all. They made five critical mistakes: 1) They should have turned back as soon as things got sketchy, 2) They were not prepared for winter travel in the backcountry, 3) They did not have the skills necessary to be in the environment in the first place, 4) and they did not have plans to address emergencies should something go wrong.

Remember, we’re not talking about a summer hike up the Hidden Lake Trail. We’re talking about being out overnight 17 miles into Glacier National Park wilderness in October.

To reiterate, I'm happy they are alive. I am grateful to the searchers who saved them. But please, let’s not glamorize folks who make huge mistakes and poor decisions as heroes. These two men put themselves in the position to get into serious trouble by not knowing their limits, taking on too much risk, and not having a back-up or bail plan. That is inexcusable. That’s called preparing to cause and incident. Let’s say what it really is, a lesson for all -- about staying put when you're lost, but more than that it’s about not going into as situation you can’t handle on your own.

I hope, as we see these guys making their rounds on the morning talk shows to gloat about their harrowing experience one mid October week in Glacier National Park that we also see them swallow their pride and tell the world about the mistakes they made rather than taking credit for being prepared and staying put when lost. They've been given a second chance at life. I’d like to see them use it to ensure no one else makes the same stupid mistakes.

Sincerely, Tony Bynum

Tony Bynum is a full-time professional outdoor photographer from East Glacier Park, MT. He has more than 25 years of backcountry experience including alpine mountaineering and has, since his first major expedition at the age of 18 where he spent 25 days crisscrossing the North Cascades on foot, lived an outdoor adventure lifestyle. He’s trained in wilderness survival and backcountry first aid. He’s led myriad backcountry trips with people whose safety was his responsibly, and he’s climbed more than a dozen peaks in Glacier National Park, including all that surround the location where the lost hikers were found. He's also a father and a compassionate friend who cares deeply about Glacier National Park and human safety. I'm also an inReach user: DeLorme inReach Two Way Satellite Communcator for Smartphones

Time Lapse Photography Video - Two Medicine Lake, Glacier National Park, Montana

Adding time lapse "video" into my outdoor photography routine brings a new dimension of creativity, one I enjoy very much. In this short time lapse video, I captured about 2000 frames of the clouds, sun and lake during one early morning adventure at Two Medicine Lake, in Glacier National Park. The time lapse took just over an hour to film and about that much time, maybe more if you count the time it took the computer to processes and export all the images, to create at home (not including upload to youtube).

This time lapse of the sun rising on Sinopah Mountain, in Glacier National Park was created with a GoPro HD HERO2:

In this time lapse video, if you watch closely at the highest resolution, you might be able to see a bear come out of the bush and walk along the far shore in the middle center right of the frame. Also, pay attention to the light coming and going on the mountains.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A8KzA-ROsdw&feature=share&list=UU9fouTHFoZMiOFQHLuml84Q

I created the final output using Adobe Photoshop Lightroom 4

Setting up the shot and getting the right kind of motion is the most challenging part of doing time lapse. The truth is you still have to get up, you still have to be there, you still have to have a compelling composition, so you still have to work hard! The post processing is a bit more work, and the entire workflow can be shortened if you have a fast computer. If you dont, be prepared to wait awhile for the computer to process the images. I generally shoot all my time lapse videos at the highest resolution I can that way I'll have more room and data to work with later. You can shoot time lapse videos at a smaller resolution and that would help cut-down on the amount of time you're sitting at your desk, but you'll have fewer editing options.

I'd like to thank my good friend, and fantastic artist www.jackgladstone.com for the music. If you're love Montana, and Glacier National Park, you'll love Jack's work. Head on over and pick up one of his CD's. Buffalo Cafe

Cheers,

Tony Bynum

Glacier National Park, Wild Goose Island Time Lapse

On Saturday, June 9th, I finally made good on a conservation donation I made almost a year ago. Back in September I donated a day with me photographing nature to the Glacier-Two Medicine Alliance. The purpose of the donation was to help raise money for the organization and help it reach it's ultimate vision, "A child of future generations will recognize and can experience the same cultural and ecological richness that we find in the wild-lands of the Badger-Two Medicine today." Fitting! Based on the request of the person who purchased the auction item - me for a day - we headed into Glacier National Park. Our first stop on that mostly cloudy and rainy day, as it turned out, was Saint Mary's Lake, and Wild Goose Island. That location is best photographed in the morning. As I was learning to photograph Glacier National Park, I once drove back and forth from Browning, MT where I was living at the time, to Saint Mary Lake 25 times over the course of 25 days just to photograph it. However, on this outing we have only one day to get it right!

As luck, or fate, since we've been good would have it, we got great light and great clouds. As I was working with my new friend, I set up another camera to capture the scene over the course of about an hour. This is a time lapse of the clouds blowing over Saint Mary Lake, and Wild Goose Island in Glacier National Park.

I like the look of time lapse, particularly when there's some motion. Notice the trees, the lake and the sky. If you want to change it up a bit, try some time lapse, it's really fun!

Remember if you're a Facebook user, you can find me Tony Bynum Photography on Facebook where I post new photos almost everyday!

Cheers!

Crown Of the Continent Magazine Features work by Tony Bynum Photography

My friend and fellow explorer and adventure Rick Graetz recently featured some of my imagery in his e- magazine "Crown of the Continent." In it Rick shares stories and the history of the Crown of the Continent Ecosystem. You can view the "crown of the continent" magazine by clicking on the highlighted text. My images start on page 19 but I encourage you to flip though the entire magazine, it's full of great content about the region I call my home. For more information about the e-magazine, Contact: Rick Graetz, UM Crown of the Continent Initiative co-director, 406-439-9277, rick.graetz@mso.umt.edu Jerry Fetz, UM Crown of the Continent Initiative co-director, 406-546-5711, fetzga@mso.umt.edu.

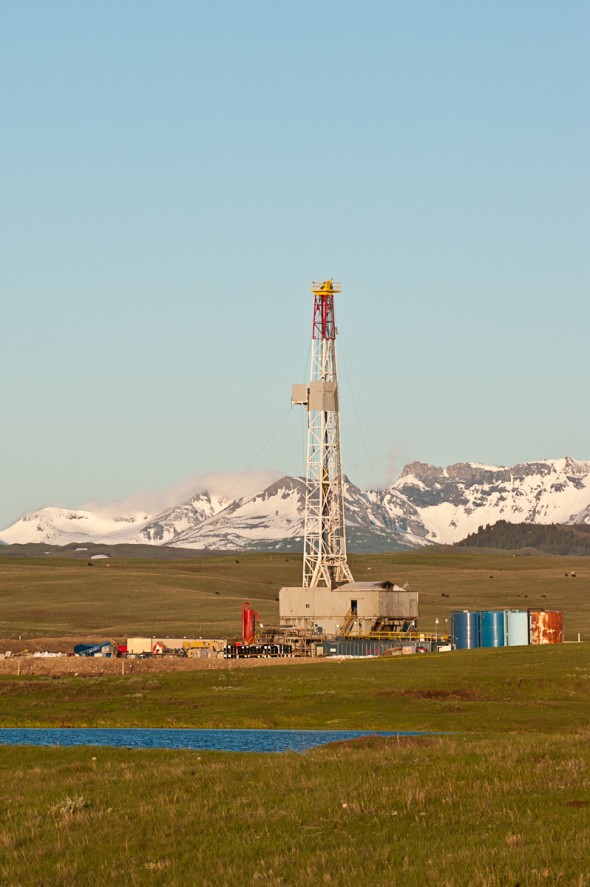

New Oil Drilling Video and Photographs from the Rocky Mountain Front

I've attached three new photographs of two drill rigs, the first two are the Red Blanket site on the Blackfeet Reservation, and third is a drill rig south of the Reservation and west of Bynum, Montana. The short video is of the Red Blanket site near Star School, west of Browning, Montana, Glacier National Park is in the background. Video - Red Blanket Drill Site

Red Blanket Well

Red Blanket well, west of Browning, Montana

Rocky Mountain Front well, west of Bynum, Montana

For a complete description of the larger project please visit, "Blackfeet oil project description." To view an interactive map of the oil drilling visit, "oil drilling map Rocky Mountain Front, Blackfeet Indian Reservation."

A Ski Photo Cover Shot with No Skier - it's simple.

This photograph was captured while working on a wolverine research project in Glacier National Park. The set of ski tracks, actually two sets of ski tracks - one over the top of the other - coming across the frozen Two Medicine Lake from a grand mountain landscape, was captured on the last day of our three-day winter back country expedition. It also landed on the cover of the January/February 2012 issue of Montana Magazine, one of my favorite Montana specific publications. So what is it about this photograph that landed it on the cover of Montana's most popular magazine? The answer is simple...and it, the photograph, is simple. Let me explain in more detail why I think the photographs works. First and foremost is the composition. The tracks lead the eye into the vanishing point where you pick up the bulging base of Rising Wolf Mountain in Glacier National Park, but it follows the Dry Creek Valley and on up to the title "MONTANA" - some would argue it's the other way around, from the title to the ski tracks, but I won’t get into that. The title anchors the ski tracks, almost compressing the photo, thereby drawing you into the image as if you could fall into it. The sky is open and blue, something I have found over the years to be particularly important to photo editors for a clean masthead. Second, contrast and tone. The deep contrast is found between the white snow and the dark, almost black, forest shadows caused in part by the sun angle. Together with the middle tone sky, the contrast and tone all work together to help balance the image. Finally, the photograph lacks an often important element to editorial photography…the presence of a human. I think this photograph works better for that reason by making the viewer ask were the skiers coming or going, and where are they now? Sometimes you don’t have to have every element in a photograph to make it work, sometimes less is more. The primary reason I took the photo was I wanted a photograph to help remind me of our epic, 25-mile mid-winter ski expedition deep into the heart of Glacier National Park. But I also wanted to show the world what Glacier Park looks like in winter. I hope I succeeded. I'll add this photograph for fun. It was taken on the same trip, and it should have its own story, but for now let’s just say that it felt strange packing two deer legs into Grizzly Bear Country. It was the dead of Winter…so thank goodness the bears were sleeping!

I'd like to thank the folks at Montana Magazine for continuing to use me for assignments and for digging into my stock and supporting a freelance outdoor adventure, nature and wildlife photographer! Tony

Oil Drilling - the Rocky Mountain Front and Blackfeet Indian Reservation

Wide open, roadless spaces, wildlife, and the people who depend on them and energy development along the Rocky Mountain Front: A Photo Record of “Progress.”

“Documenting current conditions on the Blackfeet Reservation and Rocky Mountain Front today is a very high priority. The landscape, Native American cultures, small towns,

sensitive and endangered wildlife and their habitat, are part of this complex puzzle and being altered at alarming rates.” - Tony Bynum 2010

Introduction, Setting and Scope The eastern front of the northern rocky mountains in Montana and southern Alberta occupies the interface where grizzly bears still freely move back and forth between the mountains and the prairie, is on the brink of massive change, particularly along Glacier National Parks east side. An interactive map of the current oil drilling on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation will help orient you. The eastern side of the crown of the continent ecosystem starts at the sharp jagged peaks in Glacier National Park, Waterton National Park in Alberta, CA, and the Rocky Mountain Front of Montana, where water flows to three oceans and literally divides the east and west. This area was known to the Blackfeet People as the Backbone of the World. More recently it has come to be included in a larger region known today as the Crown of the Continent ecosystem. The geographic region of concern stretches about 150 miles north to south, and 100 miles east to west. It includes the Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park, the Rocky Mountain Front, the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, and southern Alberta, Canada.

The focus now is on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation simply because that is where all the activity is now occurring. The Blackfeet Reservation maintains a rich, rare, and relatively intact system of short grass prairie, and associated wildlife, along with the steep jagged mountain ecosystem of the Rocky Mountains. In addition to the prairie-mountain landscape, the Blackfeet Indian Reservation supports a unique Native American and mixed non-Indian culture that is sure to see change as the demand for energy increases, and the oil boom progresses.

The driving force for change is the global, relentless demand for energy. In many ways, this force is impacting every system on earth, not only biophysical systems but social as well. In some real ways, the industrial oil complex holds the keys to the fate of the planet and its inhabitants. The “oil-boom” has reached this land. The industrial oil complex is already solidly established on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation and in the lands to the north in southern Alberta, Canada. The Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park shares a common border with the Blackfeet Reservation.

Oil and gas infrastructure development and wind turbines around the Blackfeet Reservation, and in southern Alberta, are expanding rapidly. Development of both resources is expected to increase markedly though the coming years. Full build-out is expected to be hundreds of new oil wells and pump-jacks, acres of wind turbines and associated infrastructure consisting of hundreds of miles of new roads, work camps, and support facilities which may including new hotels, and associated structures. Estimates are that 100-700 wells will be drilled over the next few years (12 wells are complete already with many more scheduled). Changes to this area will be unprecedented. It is not possible to know in advance exactly how the changes will play out in this setting. Still, there are enough other “oil boom” cases to safely assume they will be dramatic.

Importance of this project At this moment an opportunity exists to capture for educational and historical purposes, images of this mostly healthy, open and “intact” place. Today, we can still document the rapid transition of this cold, short grass prairie. There are progressively fewer such opportunities anywhere in the world. Such an opportunity not only is rare, it is perishable. All too commonly, journalists are in the position of creating the story after the fact, when the “good stuff is gone.” Here there is a rare opportunity to capture images of important landscapes and people before impacts occur. In this area, we still have a relatively intact mountain/prairie interface ecosystem that is home to grizzly and black bears, bull trout, Canada lynx, elk, deer, bighorn sheep, mountain goats and other elements all destined to change.

I want to emphasize that documenting current conditions on the Blackfeet Reservation and along the rocky mountain front today is a very high priority. Native American cultures, small towns, sensitive and endangered wildlife, open and un-tattered ecosystems are part of this complex puzzle and being altered at alarming rates.

The Local Aspect Small, rural communities in remote areas experience firsthand the most direct effects of commercial energy development. The Blackfeet have been on this particular landscape for at least 12,000 years. It now is a remote, mostly intact, relatively peaceful, Native American Reservation. It is the Blackfeet Nation. Now, that Nation appears to face a major energy boom and likely bust as the area changes to become an industrialized tapestry of roads, pump-jacks, evaporation ponds, cars, trucks, houses, stores and whatever else goes with it. At a minimum, it seems certain that once the fields are fully built-out, not only will the land not look the same, it’s people will never again behave the same. This project will document and share images of this landscape and its people before, during, and after the build-out of an intensive, high-cost, industrial energy system comprised of wind turbines, drill and “fracking rigs,” new roads and facilities, along with other associated activities and change. Already, some images of current conditions have been produced in anticipation of this larger project. They form the beginning of a vital baseline that must be established before the land and the people are dis-aggregated, the roads are constructed and the land, water, and wild grizzly bears become scarcer or worse, memories.

The anticipated time frame for my project is 2010-2020. Filming is already underway with about two years completed. The first images are of a relatively intact landscape followed by photos of “progress.” Drilling, drillers, the local economy and the social impacts over the lifetime of the project will follow. The photographs will be used now to help educate people about this threatened region. At the same time, the project will build a digital archive for future generations who can better understand what the land looked like before and during the period of disturbance. Both digital and print images will be created and widely shared with organizations and the public though online media, social networks, web blogs, and personal presentations. Once the road’s are in, the well pads created, the drill rigs erected, ponds dug, the power lines strung and the turbines begin churning, the current largely unobstructed landscape will be a memory. Memories are all that is left when you no longer can see something in person. Images sharpen and stimulate memories. Images are likely to persist through longer spans of time and are more dependable than memories.

The anticipated time frame for my project is 2010-2020. Filming is already underway with about two years completed. The first images are of a relatively intact landscape followed by photos of “progress.” Drilling, drillers, the local economy and the social impacts over the lifetime of the project will follow. The photographs will be used now to help educate people about this threatened region. At the same time, the project will build a digital archive for future generations who can better understand what the land looked like before and during the period of disturbance. Both digital and print images will be created and widely shared with organizations and the public though online media, social networks, web blogs, and personal presentations. Once the road’s are in, the well pads created, the drill rigs erected, ponds dug, the power lines strung and the turbines begin churning, the current largely unobstructed landscape will be a memory. Memories are all that is left when you no longer can see something in person. Images sharpen and stimulate memories. Images are likely to persist through longer spans of time and are more dependable than memories.

To document the entire build out over the coming years I plan to photograph the story from both the land and the air, and with both stills and video. I will follow and record a few specific people as well. I'll shoot and post/publish regularly in order to generate and maintain interest. The campaign will be driven both online and in person. As is so effective today, social media: for examples, Twitter, Facebook, Linkedin, will be an important vehicles. I will employ my personal network along with the much larger network of the people and conservation organizations who care about this place and project - basically everyone who pays attention to natural ecosystems, and likes cowboys, Indians, wildlife, and glaciers.

Cost of this project for year one and two is estimated to be $40,000. The costs include expenses for local travel, fixed wing airplane rental, assistance in the field and office when necessary (mainly web design and development, and continued costs for hosting and management), some special equipment including a ground based radio controlled aerial platform. The aerial platform will enable me to capture low level aerials that offer a better perspective of the relationship between the development and the landscape. It will also be more cost effective, and I can react to local weather conditions and shoot aerials without always the need for a fixed wing aircraft. The remainder will pay for time to capture, process, market and produce the project.

About Me

Education, Science and Business Tony lives in East Glacier Park, MT on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation with his 9 year old daughter. He has more than 20 years of professional and executive environmental management experience. He holds a Master's of Science in Resources Management degree, an undergraduate degree in Geography and Land Studies, and a minor in Environmental Studies from Central Washington University. Tony has managed more than 30 complex scientific research projects for the Environmental Protection Agency from coast to coast, he’s worked in the private sector and for Indian Tribes and non-profits. Over his 20 year professional science career he has participated in the development of countless environmental policies and/or regulations from the EPA, to the USFS, BLM, DoD, DOE, BOR, Washington State’s DOE Wetlands mitigation banking regulations, air and water quality plans, and more. Tony’s a board member of the professional outdoor media association, the East Glacier Park School Board, and a current member and former officer on the East Glacier Park Volunteer Fire Department and a principal member of the Glacier Two Medicine Alliance.

Tony lives in East Glacier Park, MT on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation with his 9 year old daughter. He has more than 20 years of professional and executive environmental management experience. He holds a Master's of Science in Resources Management degree, an undergraduate degree in Geography and Land Studies, and a minor in Environmental Studies from Central Washington University. Tony has managed more than 30 complex scientific research projects for the Environmental Protection Agency from coast to coast, he’s worked in the private sector and for Indian Tribes and non-profits. Over his 20 year professional science career he has participated in the development of countless environmental policies and/or regulations from the EPA, to the USFS, BLM, DoD, DOE, BOR, Washington State’s DOE Wetlands mitigation banking regulations, air and water quality plans, and more. Tony’s a board member of the professional outdoor media association, the East Glacier Park School Board, and a current member and former officer on the East Glacier Park Volunteer Fire Department and a principal member of the Glacier Two Medicine Alliance.

Tony owns Tony Bynum Photography & Glacier Impressions Gallery. In 2004 Interior Secretary Gail Norton appointed Tony to the Montana Resources Advisory Council (federal advisory committee, member 2 years, chairman 1). During that time, from 2005 until early 2010 he also managed complex scientific research projects at Portage, a private consulting firm. From 1999 to 2001 he was a special assistant and the acting Senior Indian Program Manager at EPA in Washington, D.C., responsible for a $2 Million budget, implementing federal statutes, strategic planning, GPRA reporting, and federal rule making. In 1997 and 98 he was the co-chair of the technical oversight committee of the Western Regional Air Partnership.

Bynum’s images have appeared on the covers and in copy of many of the countries major traditional outdoor recreation focused magazines, including Field & Stream, Outdoor Life, Sports Afield, Fair Chase, Texas Sporting Journal, Eastman’s Hunting, and Eastmans Bow hunting, Bugle, Bowhunt America, Montana Outdoors, Montana Magazine, Western Hunter, Western Horseman, and many more. Tony recently became the photo editor for Elk Hunter Magazine and In 2010 he was selected to produce commercial advertising images for the State Of Montana’s Office of Tourism. His images are currently display on buses, trains, billboards, windows, skylights, and elevator doors from Chicago to Seattle, WA.

His list of publication credits is extensive including other industry publications like, National Geographic, the NewYorker, The Food Network Magazine, Popular Photography, Digital Photographer (UK), Delta Sky, Empire Builder and many, many more (complete list between 2009-2011).

Tony’s often hired to produce unique, compelling, thoughtful images to compliment editorial writing in magazines and books. He has worked or traveled to all of the lower 48 states, Mexico, and much of Canada, and writes regularly for his blog. He’s active on Twitter, Facebook, Linkedin, Behance, and moderates and edits photography, outdoor activities and hunting forums on several very popular websites.

Current Interests and Positions 1. conservation photography and the Rocky Mountain Front 2. board member of the Professional Outdoor Media Association 3. board member of the East Glacier Park School District 4. member and past training officer on the East Glacier Park Volunteer Fire Department 5. principal member of the Glacier Two-Medicine Alliance. 6. Author of the blog, www.glacierparkphotographer.com 7. regularly consults with the TWS, the Montana Wilderness Associating, the Montana Wildlife Association, the Coalition to Protect the Rocky Mountain Front, and many other state and national conservation and resource management organizations/groups.

Personal Commitment Central to Tony’s lifestyle is giving something back. As a young man he decided that giving was an essential part of his core belief. To him, giving is a lifestyle choice; it’s more than a duty. There are few things more rewarding or more valuable than offering yourself up to help others. If his entire life were mapped topographically, the ridges would represent the edges of his experience, while the blue line in the valley bottom would signify his giving; it’s central to his life and like the river at the bottom of the valley, all things run though it.

Tony has a unique, and truly authentic set of real-time, current and tested skills in business, management, governance, science, writing, communications, technology, social leadership and teaching. He’s a trained facilitator and has served on three boards where consensus was the agreed processes for decision making. He’s an educator, a leader by nature, a father, and a great friend.

"In the end we will conserve only what we love. We love only what we understand."

- Baba Dioum

A Blackfeet Oil Drilling Press Kit containing project information and photographs to accompany your story is available.